And I caught a glimpse of the future.

Last week I was in New York for World to NYC and I happened to try Google Glass in the NY Tech Meetup. World to NYC is a program hosted by NYC EDC, New York City’s arm for economic development which invites founders from across the world to get to know the NYC startup ecosystem, companies, and investors.

I never had met Jonathan Gottfried previously. But I knew him online because of his work as a developer evangelist at Twilio. We accidentally met at a startup booth in the NY Tech Meetup after-party in NYU. I asked him about trying Glass out — he was kind enough to say yes (thanks, Jon!) We went outside the big meetup room and into the floor lobby in order to not get swarmed by other people eager to try out Glass. Turns out, we did.

Let me point out that this post is more of a long essay about Glass, its future as a product and what it means for our society, rather than a simple review. Since I wore it for about 5 to 10 minutes I’m not in a position to review it.

If you follow me over on Twitter or read this blog quite frequently you already know by now how much I love Glass and the promise it carries.

There’s a Glass narrative which stretches back to July 2012. In The Next Big Thing (November, 2012) I was writing:

The most profound and quick answer that comes to my mind is Google Glass. I love its potential. And for the nay-sayers: no, you don’t look stupid, on the other hand it’s pretty cool — you look like Vegeta and, please, oh please, just imagine the potential. Retina-embedded layers.

When analyzing the tech stocks and the industry in Facebook, Google and the Stock Market (July, 2012) I was writing:

Google magically transformed and managed to inspire again. Project Glass has a gigantic potential, radically transforming our lives with entirely new paradigm shifts.

And, finally, in a 1,400-words post about the then current mobile landscape and the war between Apple and Google (January, 2013) I was writing:

Google Glass is the next big step for Google. […] from a product and tech perspective it is one of the most truly exciting things out there. And it can easily integrate with Google’s data pool, hence capitalize it and push “personalization” to a whole new level. […] Google Glass will be everywhere with you.

[…] most importantly, Google Glass will be a landmark event in Google’s history. It will depict the transition between a web/software company, from producing stuff that “doesn’t exist,” to stuff that does actually exist […] This event enables Google to capitalize a lot more on its data: use it as a generator of products both of software and hardware nature. And hardware might be a hard problem to tackle, but even at the early stages of Google Glass, we see that Google can indeed tackle it.

From the aforementioned quotes I’ll note down the following: “gigantic potential,” “retina-embedded layers,” “landmark event,” and “paradigm shift.” These few words, I think, describe in an essence all what Glass stands for. And before I jump to abstract techno-utopian philosophical conclusions about the digital nature and future of our lives and society let me first describe how Glass works and feels like.

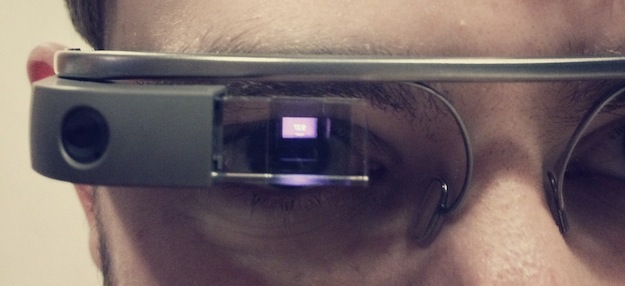

It is lightweight. Extremely lightweight. It never feels like you’re wearing something on top of your ears and nose. More importantly, it doesn’t block your normal optical vision. When Glass sleeps (hint: most of the time if you’re not using it) it’s like it’s not even there. It truly gets out of your way — and that’s remarkable for a physical thing that exists on top of your head and in front of your eyes.

Overall, its physical design is small; yet big. And by that I mean: it is small as a hardware device, especially considering its right part which includes the battery (which, I think, lasts for about a day) and the touch interface to navigate through menus and options by swiping up / down, left / right. However, it is still big in the sense of how smaller it can (will) be in future versions given the hardware progress we can naturally depend on Google making soon.

“Ok, glass…” — this is how the future sounds like. Google, Take a picture, record a video, get directions to, send a message to. These are the basic voice commands for Glass right now. There are also “make a call,” “hang out” (you guessed it right — video calls through Google Plus’ Hangout service) and more. You can also use “ok, glass, google …” in very powerful ways, just like you’d do on the web.

The display feels more like a holographic video projection between two pieces of glass rather than a monitor. Its color quality is not perfect and a little bit below of what you’d normally expect but it’s still version #1. Naturally, there’s a lot of room for improvement in the future. I’m certain this will get better. Below there is a video I recorded with “ok, glass record a video.” Unfortunately Jon couldn’t find a couple of other photos I took and I can’t upload them. But basically this is the real deal; raw Glass HD video from the NY Tech Meetup.

Here’s also a summary of what Glass can do as of now:

- Take, display photos

- Record, play videos

- Read and respond to email, texts, and Gtalk chats

- Make and receive phone calls

- Perform video chats with Google+ Hangouts

- Turn-by-Turn Driving, Biking, and Walking directions

- Personalized suggestions and information from Google Now based on your Google account history and activity

- Google search

- Download and run 3rd-party apps such as New York Times, Evernote, and more

- Browse your recent activity history over a several day period

Glass wouldn’t be nearly as great without 3rd-party apps. Exactly like the iPhone and its App Store. Currently, there’s a limited selection of said apps which includes (but I’m not sure if it’s limited to) Glass Feed (post directly from your Glass to an RSS feed using IFTTT,) New York Times (breaking news notifications,) Glass Tweet (hacked by Jon,) Glassagram (an Instagram client,) a Reddit one, Evernote, Gmail and Path. You can find more about them in this proto-directory. I’m sure there are more to come since Google released an SDK. There are also some other cool upcoming features like 360-sphere photos, snapping photos with just a wink of your eye, and facial recognition. On a relevant note about facial recognition: how about making a facial recognition technology which works sans ‘facial?’ This extremely interesting paper from Duke University explains it all: InSight: Recognizing Humans without Face Recognition (pdf link) (which I recommend to at least adding it in your Instapaper/Pocket/bookmarks.) In a test of 15 people, it was able to recognize them 93 percent of the time. It’s not integrated directly into Glass yet: it’s a smartphone app that connects to the camera via Bluetooth and displays functions on top of Glass.

Aside apps, there is also this amazing design concept about Glass and how it can visualize questions, actions, and real-time environment data. Designer Jack Morgan writes:

Google Glass is years ahead of its time, but to me it just means that the future is already here, and it’s a future that’s made of Glass.

Here are some cool photos. Be sure to check out the whole concept on his blog.

All this is merely trivial, though, when it comes to talk about Glass’ context. Sure — more and better features, better display, more ‘social’ and personalization, more reddit cats right in front of your eyes, people of the internets. Features and upgrades like these will come down the road. Plus, more wearable computing devices by competitors. And, ultimately, that’s good for us.

But Glass is something much more than a new market/industry/vertical defining gadget. In the grand scheme of things, it’s one of our baby steps to see how machines see, to augment and make exponentially more usable our world. One step closer to see like, utilize our immediate environment, and harness data with the power of machines — right in front of our eyes. More importantly, Glass signifies the potential of embedding itself in our eyes. It’ll start as contact lenses, it’ll move to something smaller, maybe at some point we’ll be born with something like Glass right within your eyes. And who knows, maybe in x years time we’ll say to kids “I remember how it was to see naturally, how all this started with a big physical device on your head” and the kids will be “Big physical device? How old are ya?!”

This future might be indeed scary and way over the freaky line for some but… this is it. And it cannot change. This is where we’re heading to. Glass is not only a landmark event for and about Google but for us, as a society and culture, as well. Not Glass itself but its concept; the heavy promise it carries. Seeing like machines is only a small percentage of the totality of new things that will be introduced and start being the norm as more wearable computing devices emerge and we’ll collectively start using them.

In the words of Alan Kay, “The computer is a medium, and like the printed book during the middle ages, has the potential to modify the thought patterns of those who are literate.” Exactly the same applies for Glass. While the need to describe more about Glass’ context allows us to use the term ”paradigm shift,” I think it’s not ideal because this implies something minuscule. ”Paradigm shift” is, I think, similar to the way we describe how mobile phones were introduced in our lives back in the late ’90s and early aughts. It was a huge change but I’m not positive it will ever be as big as and more impactful than the wearable computing devices’ one. The potential is still here though, however Glass performs market-wise. And, frankly, I have no idea if it will be a market success. Many love it, many hate it, and many more don’t understand the changes it will bring. But it’s irrelevant. Here’s the catch: no matter its performance, it will bring changes. It will re-define things, concepts, lifestyles, relationships. Relationships not only between humans but also between humans and objects. Exactly like the iPad — i.e., even if it wasn’t a best-selling device it’d still define for years to come the tablet market.

Of course, we can go on talking about techno-utopias and the co-existence of humans and machines for hours. But let me dive deeper in our contemporary world, its status quo and the issues we’re facing and maybe I’ll get back to the ‘future’ in a while. Google Glass started from something very humble in Google’s [x]Lab whose director is Sergey Brin, quite possibly also the grandfather of Glass. The idea was to fix the problem of being always needy about and distracted by our phones. It’s a hyper-connected world we live in and for some their smartphones are sometimes more important, distracting, and time-consuming than their laptops.

We’ve seen that all this technology which surrounds us, has made us prone to distractions more than ever. For example, I don’t remember the last time when I hanged out with my friends and I didn’t check my iPhone — or even my friends not checking theirs, for that matter. Our contemporary culture is heavily based on attention-seeking actions, objects, and everything in between. Sometimes it can be overwhelming. Notifications coming hourly in our phones begging for an action; “Reply me,” “View me,” “Comment me,” “Like me,” and generally all sorts of demanding stuff. From games and their useless in-app purchases about cheaper boots for your RPG character, to whom retweeted your tweet, and who added you as a friend on that obscure social networking app you downloaded the other day and still haven’t deleted it. We can do better, that’s what Brin always takes for granted. And thus Glass was born.

It is fairly easy, though, for one to argue that there’s no actual difference with Glass since everything simply changes location and medium (from your phone to Glass) and as a result comes even closer to your eyes. In fact, in front them. This approach may seem valid in the beginning, but by thinking about it a little more it is clear that it, in fact, is unsound. Glass doesn’t simply take an existing experience and replace it. It creates a new one, entirely different without the problems of the old one. For starters, when you don’t need Glass, it disappears automatically. It doesn’t get in your way, it doesn’t seek attention — Glass patiently waits for you and your commands. To fulfill them.

Core attribute of this new experience is its futuristic flare. Things don’t show up when they want but when you want them to. This is vastly different compared to the nature of mobile phones and their notification systems whether it’s iOS or Android. And when there’s nothing to show, there’s nothing to see, ergo you’re offline while always being online. Maybe our first digital hallucination — being out of the Matrix while, essentially, being inside it. Machines do know our human nature. After all, they’re the reflections ouf our dreams, hopes, virtues and vices, fears, ambitions, and most importantly, our own selves.

Everyday we’re getting closer to the machines and the machines get closer to us. They know us — we taught them how — they can predict us, they can understand us. Someday we almost won’t be able to tell the difference between us and them, unless for our own Voight-Kampff test, and all this starts right now with Glass. In essence, Glass has captured all our futuristic dreams, wishes, and aspirations spanning across generations and has started the revolution. Machines found a way on us; soon enough they’ll found a way inside us, and I for one, welcome it. It’s only a matter of time.

~

In 1967 George R. Price went to London after reading Hamilton’s little known papers about the selfish gene theory and discovering that he was already familiar with the equations; that they were the equations of computers. He was able to show that the equations explained murder, warfare, suicide, goodness, spite, since these behaviors could help the genes. John Von Neumann, after all, had invented self-reproducing machines, but Price was able to show that the self-reproducing machines were already in existence, that humans were the machines.

“And all watched over by machines of loving grace” is now more true than ever. Beautiful machines.

—

Upd: Today, just after publishing this very post I attended a guest lecture by Computer Science pioneer and legend Don Knuth here in Vienna University of Technology. It’s the first of the Gödel Lectures Series organized by our Computer Science faculty. I feel very fortunate to have met one of the greats. I asked him about machines and humans and this is his answer:

Computer Science is wonderful but it doesn’t answer everything. We, as humans, have some limitations and we should be humble and embrace them. Some spiritual things will never get an answer — that’s another whole different realm that science cannot provide an adequate answer for. And, if in fact, “we’re watched over by machines of loving grace” — if Game of Life is somehow applied in our reality and our universe — and our universe is a computer simulation, which means we’re simply mathematical representations and everything is deterministic and, as a result, we lose our free will, then there’s nothing we can do about it and we cannot answer it, thus we shouldn’t bother thinking about it. I’m grateful for the machines.

Comments

Comments are closed.